“The debate over Vietnam's occupation of Kampuchea has divided many people on the Left. The Vietnamese position, which many people in the U.S. and Canadian Left support, is that the present Kampuchean government is an independent nation. In a speech to the U.N. General Assembly on October 21, 1981, concerning a negotiated settlement to the Kampuchea problem, the Vietnamese claimed that there was no "Kampuchea problem" and

hence there could be no "comprehensive settlement." With this statement the Vietnamese were trying to ignore the real situation in Kampuchea.

Since that time, the Vietnamese have made a few proposals of their own for a negotiated settlement. These include negotiations with the non-Khmer Rouge members of the Democratic Kampuchea Coalition, a dialogue with China, and a proposal to allow some Khmer Rouge members to enter the government, provided they come in as individuals and not as a group. They still refuse to negotiate with the Khmer Rouge. This indicates that the Vietnamese now realize that the "Kampuchea problem" is no longer a problem they can afford to ignore.”

-Steve Otto, “Kampuchea Today:

A Response to Hoang Tung,”

Contemporary Marxism, no. 12 – 13, Spring 1986, p. 64

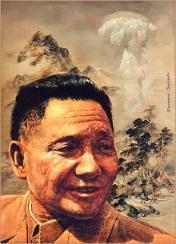

I wrote this in 1986, under the illusion that the Chinese position was the least imperialist of the two other major super-powers, The U.S. and the U.S.S.R. As with the old Lewis Carroll story Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, things were not what they appear to be. China had no real international policy other than pure self interest. Deng Xiaoping, China’s leader and an ardent supporter of Pol Pot, was a self absorbed egotists interested in his countries economic development and little else. China supported no outside Marxist groups unless they had something to offer. And Pol Pot was not part of the Chinese international, nor was he a Maoist.

In my book Memoirs Of A Drugged-up, Sex-crazed Yippie ---Tales from the 70's Counterculture: Drugs, Sex, Politics and Rock and Roll, (see review below), I discussed my illusions about Pol Pot’s revolution and what I later found out to be the truth about the four year period of Democratic Kampuchea. It was just a nationalists peasant revolution, badly blundered by its leaders, who believed they would somehow be seen in the future as being more important and greater than Maoism.

Here is an excerpt from Chapter 17- “1979 - A changed world”:

The one thing I could always count on with Ian was a good political conversation, when he wasn’t trying to pick up women. On this particular winter day, I walked into the Bier Stube and found Ian and one of his friends talking about the Vietnamese invasion and occupation of Cambodia, now called Kampuchea.

“I agree with Henry Kissinger,” Ian said. “The Vietnamese did not go into Cambodia for humanitarian reasons. They went in to take advantage of

the instability of Pol Pot’s government and then install a regime that would benefit them.”

“I can agree with that,” I said.

This was one of the few times that I did agree with Ian. It was ironic because I had discussed this matter with Shokrollah (an Iranian student) about a week earlier and he also agreed with Ian and me. Of course we agreed for different reasons.

In December of 1978 Vietnam invaded Democratic Kampuchea and overthrew its leaders. By January of 1979, they installed a new government, the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, headed by Heng Samrin. Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea government was over. His organization was pushed out into Thailand. He and his followers formed a guerrilla army of resistance. The Vietnamese kept troops and advisors in Kampuchea to help establish the new government.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

My discussion with Ian reminded me of a conversation I had had with Shokrollah about the Khmer revolution of 1975. We had just left a Friends of the Iranian People’s meeting. “I refused to just believe what a lot of reporters in the main-stream Western press are saying,” He said.

“There may be some truth to those reports, but I won’t just take their word for it. And I don’t believe they are just real vicious as the reports say. That sounds like propaganda to me.”

I finally had to agree with him that the reports deserved some skepticism. The Western press was biased enough that if no one had been killed during that government, I seriously believe the press reports would have been almost the same. I had learned to be skeptical of foreign reporting. Shokrollah was even more so. At first, I took the press reports for their face value; that Pol Pot was really mean. He killed a lot of people and banned just about anything a person, as myself, would like to do, such as listening to rock music. But after talking to Shokrollah, I began realizing that people from third world countries might see things differently. I decided to try to see the other side. I too began to question all the horror stories and noticed that certain leaders were singled out as brutal and evil who just happened to be opponents of US foreign policy. The Shah (Mohammad Reza Pahlavi) of Iran and Chile’s (Augusto) Pinochet were rarely, if ever, singled out for their torture and murder of political prisoners. Only opponents of US foreign policy were. Many foreign students told me Uganda’s (Idi ) Amin was brutal, but he also took a stand against imperialism. It was for that stand, they said, that Western journalists and politicians focused on his human rights abuses. After gaining an appreciation for Maoist philosophy, I was intrigued with the idea of a miniature Maoist revolution in Kampuchea. I began to notice the far-left tendencies of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, which the press called the Khmer Rouge. It was the only other Maoist revolution to succeed in the world at that time. Kampuchea’s rulers eliminated money and private property. Democratic Kampuchea seemed fiercely independent, even though it got some military aid from China. For some time, I had mixed feelings about Pol Pot. On one hand, his movement seemed to be far to the left and yet there was no justification for those executions. I was also puzzled. I was so impressed with the philosophy of Mao, I couldn’t understand how a government that tried to imitate it could produce such a disaster. It was during the Cultural Revolution that Mao and Chiang Ching broke with Marx’s view that everything is based on economics. They insisted that ideas are more important than material things. That was a view that I agreed with. How could Kampuchea go so terribly wrong?

What I didn’t realize at the time was that the Kampuchea regime was not Maoist. It had an alliance with China but the CPK considered itself an ideological rival rather than having fraternal ties with the Chinese Communist Party. China simply needed Democratic Kampuchea to counter Vietnam’s expansion. The CPK’s views on Marxism were muddled and poorly developed. Most of the ideological documents of Pol Pot and his CPK were kept secret from all those outside the party, both inside and outside the country. They began leaking out of the country starting in 1979. Most of their ideology was summed up in two documents, Decisions of the Central Committee on a Variety of Questions and The Party’s Four-Year Plan to Build Socialism in All Fields, 1977 - 1980.

By 1979, both Shokrollah and I began to see that Democratic Kampuchea had some serious problems.

“They made a lot of mistakes,” Shokrollah said one night after our meeting. “They didn’t tolerate any of the nationalist bourgeoisie, which they may have needed in the short run. They should not have arrested (Norodom) Sihanouk, who was progressive and had a popular following. The fact that they fell so fast showed they lacked popular support. But that was no excuse to invade the country and occupy it as Vietnam did.”

Vietnam was clearly in the Soviet camp by now, which he considered “socialist imperialists” and “state capitalists.” Shokrollah was good at analyzing politics. I was surprised to find that he and some of the Marxist Iranians had read Sartre, which they considered important reading. Sartre’s ideas of pleasure had some similarities to that of the Cyrenaics, while other Marxist writers the Iranians read had more puritanical views on sex and drugs.

Ian and Shokrollah were polar opposites when it came to politics. Ian’s politics were also the opposite of mine. However he did like to drink and chase women, which was one thing we had in common.

interesting read

ReplyDeleteInteresting post, enjoyed the stuff on Deng Xiaoping and CCP's relation to Cambodian killing fields. I disagree, however, with your claim that Pol Pot was "no Maoist." In fact, his project of forcible ruralization is in keeping with the essence of Maoism (peasant revolutionism).

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteI can recommend a book “Pol Pot plans the Futurere,” by David P. Chandler, Ben Kiernan and Chanthou Baua, Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, 1988. It provides the documents written by Pol Pot and his committee. According to this book they did talk of the CPK of using slogans and some ideas they clearly borrowed from Mao, but gave him no credit for those ideas. They used the slogan ”Super Great Leap Forward” as an attempt to up-one on Mao who once used the slogan “Great Leap Forward.”

ReplyDeleteOn a TV biography of Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, the former foreign minister of Democratic Kampuchea, said that he attended a visit to China with Pol Pot, during the cultural revolution. Pol Pot remarked when they got back that Mao “Didn’t know what he was doing.” Ieng Sary also said: “We talked communism, but we were really talking nationalism.”

I also recommend “What Went Wrong with the Pol Pot Regime,” A World To Win at http://www.awtw.org/back_issues/1999-25/PolPot_eng25.htm.

It explains many of the differences between Pol Pot, who warned his followers to avoid all foreign theoreticians and Mao.

It is important, even if some similarities exist, to acknowledge that the CPK saw itself as a completely different kind of entity than the leadership of China.